Our torture policy has deeper roots in Fox television than the Constitution.

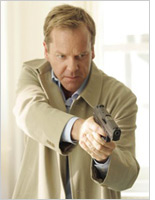

The most influential legal thinker in the development of modern American interrogation policy is not a behavioral psychologist, international lawyer, or counterinsurgency expert. Reading both Jane Mayer's stunning The Dark Side and Philippe Sands' The Torture Team, I quickly realized that the prime mover of American interrogation doctrine is none other than the star of Fox television's 24: Jack Bauer.

This fictional counterterrorism agent—a man never at a loss for something to do with an electrode—has his fingerprints all over U.S. interrogation policy. As Sands and Mayer tell it, the lawyers designing interrogation techniques cited Bauer more frequently than the Constitution.

According to British lawyer and writer Philippe Sands, Jack Bauer—played by Kiefer Sutherland—was an inspiration at early "brainstorming meetings" of military officials at Guantanamo in September of 2002. Diane Beaver, the staff judge advocate general who gave legal approval to 18 controversial new interrogation techniques including water-boarding, sexual humiliation, and terrorizing prisoners with dogs, told Sands that Bauer "gave people lots of ideas." Michael Chertoff, the homeland-security chief, once gushed in a panel discussion on 24 organized by the Heritage Foundation that the show "reflects real life."

John Yoo, the former Justice Department lawyer who produced the so-called torture memos—simultaneously redefining both the laws of torture and logic—cites Bauer in his book War by Other Means. "What if, as the popular Fox television program '24' recently portrayed, a high-level terrorist leader is caught who knows the location of a nuclear weapon?" Even Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, speaking in Canada last summer, shows a gift for this casual toggling between television and the Constitution. "Jack Bauer saved Los Angeles. … He saved hundreds of thousands of lives," Scalia said. "Are you going to convict Jack Bauer?"

There are many reasons that matriculation from the Jack Bauer School of Law would have encouraged even the most cautious legal thinkers to bend and eventually break the longstanding rules against torture. U.S. interrogators rarely if ever encounter a "ticking time bomb," someone with detailed information about an imminent terror plot. But according to the Parents' Television Council (one of several advocacy groups to have declared war on 24), Jack Bauer encounters a "ticking time-bomb" an average of 12 times per season. Given that each season allegedly represents a 24-hour period, Bauer encounters someone who needs torturing 12 times each day! Experienced interrogators know that information extracted through torture is rarely reliable. But Jack Bauer's torture not only elicits the truth, it does so before commercial. He is a human polygraph who has a way with flesh-eating chemicals.

It's no wonder high-ranking lawyers in the Bush administration erected an entire torture policy around the fictional edifice of Jack Bauer. He's a hero. Men want to be him, and women want to be there to hand him the electrical cord. John Yoo wanted to change American torture law to accommodate him, and Justice Scalia wants to immunize him from prosecution. The problem is not just that they all saw themselves in Jack Bauer. The problem was their failure to see what Jack Bauer really represents in relation to the legal universe of 24.

For one thing, Jack Bauer operates outside the law, and he knows it. Nobody in the fictional world of 24 changes the rules to permit him to torture. For the most part, he does so fully aware that he is breaking the law. Bush administration officials turned that formula on its head. In an almost Nixonian twist, the new interrogation doctrine seems to have become: "If Jack Bauer does it, it can't be illegal."

Bauer is also willing to accept the consequences of his decisions to break the law. In fact, that is the real source of his heroism—to the extent one finds torture heroic. He makes a moral choice at odds with the prevailing system and accepts the consequences of the system's judgment by periodically reinventing a whole new identity for himself or enduring punishment at the hands of foreign governments. The "heroism" of the Bush administration's torture apologists is slightly less inspiring. None of them is willing to stand up and admit, as Bauer does, that yes, they did "whatever it takes." They instead point fingers and cry, "Witch hunt."

If you're a fan of 24, you'll enjoy The Dark Side. There you will meet Mamdouh Habib, an Australian captured in Pakistan, beaten by American interrogators with what he believed to be an "electric cattle prod," and threatened with rape by dogs. He confessed to all sorts of things that weren't true. He was released after three years without charges. You'll also meet Maher Arar, a Canadian engineer who experienced pretty much the same story, save that the beatings were with electrical cables. Arar was also released without explanation. He's been cleared of any links to terrorism by the Canadian government. Jack Bauer would have known these men were not "ticking time bombs" inside of 10 minutes. Our real-life heroes had to torture them for years before realizing they were innocent.

That is, of course, the punch line. The lawyers who were dead set on unleashing an army of Jack Bauers against our enemies built a whole torture policy around a fictional character. But Bauer himself could have told them that one Jack Bauer—a man who deliberately lives outside the boundaries of law—would have been more than enough.

No comments:

Post a Comment