The future of the detention facility on the American naval base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, inspires an unusual degree of bipartisan consensus, at least in theory. All three remaining candidates for President, the Republican John McCain and the Democrats Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, have called for Guantánamo to be closed. So have Condoleezza Rice, the Secretary of State, and Robert M. Gates, the Secretary of Defense; after touring Guantánamo in January, Admiral Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, “I’d like to see it shut down.” At a news conference in 2006, President Bush said, “I’d like to close Guantánamo.”

Still, Guantánamo is bustling. Although the number of detainees has fallen from a high of around six hundred and eighty to around two hundred and seventy-five, the base is gearing up for what could become a series of military commissions—criminal trials of detainees. The first is scheduled to begin in May. On a dusty plaza surrounded by barbed wire on an abandoned airfield, contractors are finishing a metal warehouse-type building, which will house a new, highly secure courtroom. On the former runways, more than a hundred semi-permanent tents have been erected, in which lawyers, journalists, and support staffs will work and sleep (six to a tent) during the trials. The tent city has been named Camp Justice. The Bush Administration, instead of closing Guantánamo, is trying to rebrand it—as a successor to Nuremberg rather than as a twin of Abu Ghraib.

The commission trials will be the latest act in a complex legal drama that began shortly after September 11, 2001. A few weeks after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the United States invaded Afghanistan, and on November 13, 2001, President Bush issued an order establishing military commissions to prosecute war crimes by members and affiliates of Al Qaeda. On January 11, 2002, the first prisoners from Afghanistan reached Guantánamo, which was at the time a sleepy Navy facility used for refuelling Coast Guard vessels. The Bush Administration made it clear that it did not believe that the detainees were entitled to any Geneva-convention protections. Then as now, the Bush Administration asserted that they could be held until the “cessation of hostilities,” meaning not the war in Afghanistan but the “global war on terror”—that is, indefinitely.

From the moment Guantánamo opened, it has been a target of criticism around the world. In 2005, the Amnesty International secretary-general said that “Guantánamo has become the gulag of our times, entrenching the notion that people can be detained without any recourse to the law.” There were allegations of excessively harsh interrogation practices at the detention center in its first years of operation, and the Army’s own reporting has substantiated at least one case of abusive treatment. There have been four apparent suicides at the camp and many more attempts. Even staunch American allies, like Tony Blair, in Great Britain, and Angela Merkel, in Germany, have criticized the facility. As McCain said in 2007, “Guantánamo Bay has become an image throughout the world which has hurt our reputation.” It is that sort of damage, as much as what has gone on at Guantánamo, that has prompted the calls for the closing of the facility.

Administration officials hope that the military commissions will change Guantánamo’s reputation, but that seems unlikely. To date, the commissions have been an abject failure; in more than six years, they have adjudicated just one case—a plea bargain for David Hicks, a former kangaroo skinner from Australia. In March, 2007, after more than five years in custody, he pleaded guilty to “material support to terrorism,” and was sentenced to nine months; he was returned to Australia, where he served out his sentence, and has now been released. Charges have been filed against fifteen detainees, but even if these cases come to trial—and considerable legal obstacles remain—many more prisoners will be left in limbo, without any charges pending against them or any foreseeable prospect of release. As the clatter of construction work shows, it is easier to talk about closing Guantánamo than to do it. Even shuttering it would not settle the most fundamental question raised by this notorious prison: what to do with its inmates. And attempts to resolve that dilemma are increasingly likely to play a role in the Presidential election.

Four times a week, a twelve-seat propeller plane belonging to Air Sunshine, a small airline based in Florida, lands at Guantánamo. The flight from Fort Lauderdale, just three hundred miles away, takes three hours, because the American airliner must avoid Cuban airspace. More than two thousand people work there; most are Navy and Army personnel, and about twelve per cent are civilian contractors. As in many military bases around the world, the local commanders compensate for Guantánamo’s isolation with a kind of hyper-Americanism. There are half a dozen fast-food restaurants, two outdoor movie theatres, miniature golf, and a bedraggled, but playable, nine-hole course. The roads are full of “Gitmo specials”—broken-down heaps that are traded to newcomers by people at the end of their tours.

Heading west from the base’s townlike center, you pass the first of its infamous landmarks—Camp X-Ray. A connected series of open-air cages surrounded by barbed wire, X-Ray was the destination for Guantánamo’s first prisoners. Photographs of these orange-suited detainees, many hunched over in awkward positions, became emblems of the base. The number of prisoners quickly exceeded the capacity of Camp X-Ray, and it was closed in April, 2002. Base leaders have long wanted to tear down the camp, but a federal judge, who is presiding over one of the many pending cases regarding Guantánamo, ordered X-Ray preserved as possible evidence. So the camp remains, filled with trash and overgrown with weeds.

Fifteen minutes farther down the road, overlooking a particularly beautiful rocky beach, is Camp Delta, the prison complex for the remaining detainees. When I first visited Guantánamo, in late 2003, most of the detainees were held in three areas of Camp Delta, Camps 1, 2, and 3, which look like higher-tech versions of Camp X-Ray. The detainees spent their days and nights in open-air cells, which were topped by metal roofs and surrounded by layers of barbed wire. Now, with fewer prisoners, these camps appear almost empty. (The camp authorities will not specify how many people are in each camp.)

About two dozen “highly compliant” prisoners are being held in Camp 4, which features a dusty courtyard in which inmates can move freely during the day and dormitory-style sleeping arrangements. The prisoners in Camp 4 also have access to a small library for books and movies (a National Geographic film about Alaska is popular), and they can take classes to learn to read and write Pashto, Arabic, and English.

The biggest change to Guantánamo has been the completion of Camp 5, in 2005, and Camp 6, the following year. Most of the detainees now reside there. They are modern federal-prison structures, brick-for-brick copies of a pair of existing facilities, one in Terre Haute, Indiana, and the other in Lenawee, Michigan. The scenes inside, for better or worse, resemble those at most Supermax facilities. The prisoners spend about twenty-two hours a day inside climate-controlled, eight-foot-by-twelve-foot cells, with no televisions or radios, and generally leave only for showers or for recreation in small open-air cages.

Painted on the floor of all cells are arrows pointing toward Mecca, and through the cell doors the detainees can hear each other pray five times a day. Each tier of cells appoints a prayer leader who gets a sign—“Imam”—on his door. About two years ago, there were a hundred detainees on hunger strikes demanding an end to their terms, or at least a finite sentence; the number has declined to about ten, although one inmate has been refusing food for more than eight hundred days, and another for nine hundred days. (These prisoners are force-fed twice daily, via a tube through the nose.) Interview rooms for interrogations are outfitted with blue couches for the detainees. Camp 6 had been intended as a medium-security alternative to Camp 5, but after a series of near-riots by the detainees, in 2006, it, too, was converted to maximum-security status. The so-called “high value” defendants are held at Camp 7. This is a secret location at the base and is never shown to reporters.

In a trailer “inside the wire,” adjacent to Camp 4, I spoke with Bruce Vargo, the Army colonel who runs the detention facility. “I think any facility matures over time, and I think that we’ve continued maturing and offering more programs to them, like the library,” he told me. “But they are still very dangerous men, and they take every opportunity they can. There are still assaults that take place weekly on the guards. Every day we have ‘splashings,’ so I made sure the guards have face shields to protect themselves from feces and urine.”

The catchphrase that Vargo and others at Guantánamo often used when describing their work was “safe and humane care and custody.” It was clear, however, that winning hearts and minds is not part of the agenda. “They wouldn’t be the type of people they are without being driven,” Vargo said. “They obviously are very intent on pursuing their cause. They will let you know that this place is just an extension of the battlefield.” He went on, “I would not say that we are building a fan base for the U.S. here. We are keeping bad guys off the battlefield.”

Vargo’s comments reflect the unchanging perspective of the Bush Administration, which holds that these detainees are, in the words of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, “the worst of a very bad lot”—incorrigible soldiers in an unending war. But, in the absence of any meaningful due process, there is no proof that they are. Benjamin Wittes, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, has made a comprehensive review of the prisoners for his forthcoming book, “Law and the Long War.” For a period in 2006 when Camp Delta held about five hundred prisoners, Wittes examined all the available data—including the military’s assertions about the prisoners and any statements that they themselves made—and estimated that about a third of the detainees could reasonably be said to be terrorists or enemy fighters.

The legal battle over Guantánamo has followed a trajectory similar to the political fortunes of the Bush Administration as a whole. The first court challenges by lawyers representing detainees were filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights, the left-leaning legal-advocacy group in New York, and Joseph Margulies, a civil-liberties attorney. Now, however, the anti-Guantánamo cause has gone mainstream, and Air Sunshine flights often ferry attorneys from white-shoe law firms to visit their detained clients. Almost all the remaining detainees who want attorneys are represented by American counsel.

Initially, government lawyers asserted that because the detainees were held outside the United States they had no right to challenge their status in American courtrooms, or even to file writs of habeas corpus. The Presidential order of November 13, 2001, said that the detainees “shall not be privileged to seek any remedy or maintain any proceeding, directly or indirectly . . . in any court of the United States.” But, in 2004, the Supreme Court ruled, in Rasul v. Bush, that, because the Guantánamo base was under the exclusive control of the U.S. military, the detainees were effectively on American soil and had the right to bring habeas-corpus petitions in federal court. As Justice John Paul Stevens said in his opinion, the federal courts “have jurisdiction to determine the legality of the Executive’s potentially indefinite detention of individuals who claim to be wholly innocent of wrongdoing.”

In response to Rasul, the Department of Defense created a Combatant Status Review Tribunal, an administrative proceeding to justify each detainee’s “enemy combatant” status. According to the rules, however, the detainees are not entitled to counsel, are not allowed to see all the evidence against them, and receive only the opportunity to be present and, if they choose, to respond to unclassified charges against them.

These days, the review tribunals are conducted in a windowless double-wide trailer inside the wire, under the supervision of a Navy captain named Ken Garber. These are not trials but a rough cross between grand-jury and probable-cause hearings. Three officers preside over each tribunal, and they can recommend continued detention or transfer to another country. There is only a limited right to appeal, but each detainee receives an annual review of his status in another hearing. “We look at two questions,” Garber told me above the hum of the air-conditioners. “Are they still a threat? Do they still have intelligence value? A yes to either one is enough to keep them.” The tribunals have been widely criticized as one-sided—Eugene R. Fidell, a noted American expert on military law, has called them a “sham”—and, according to Garber, last year only thirteen per cent of the detainees agreed to participate in or attend their own annual review hearings.

The commissions, which were meant to serve as criminal trials for the detainees, have so far proved to be even more dubious. After the Rasul case, in 2004, the military began pretrial proceedings in the first of the military commissions. One defendant, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, who was alleged to be a driver and bodyguard for Osama bin Laden, challenged the procedures for the commissions, and in June, 2006, he won his case before the Supreme Court. In another opinion by Stevens, the Court held Bush’s order of November 13, 2001, as it related to military commissions, to be invalid, because the President could not create the commissions without the explicit assent of Congress. Stevens also rejected Bush’s long-standing contention that the Geneva conventions did not apply to the detainees.

Bush’s response to the ruling was notable both for what it revealed about the Administration’s stance on Guantánamo and for what it might mean for the politics of 2008. Far from being chastened by another rebuke from the Justices, Bush used the Hamdan case to return to the subject of the September 11th attacks and to challenge Congress to ratify his aggressive approach. In a carefully choreographed ceremony in the White House on September 6, 2006, Bush made a surprise statement. “We’re now approaching the five-year anniversary of the 9/11 attacks—and the families of those murdered that day have waited patiently for justice,” he said. “So I’m announcing today that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and eleven other terrorists in C.I.A. custody have been transferred to the United States Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay.” All had previously been held in secret C.I.A. prisons. Despite the skepticism that Bush and his team had expressed about Guantánamo, the President had, by placing the nation’s most notorious terrorist suspects there, given the detention facility a new vote of confidence.

Bush also announced that he was sending a bill to Congress to re-create the military commissions that the Supreme Court had just struck down. “As soon as Congress acts to authorize the military commissions I have proposed, the men our intelligence officials believe orchestrated the deaths of nearly three thousand Americans on September 11, 2001, can face justice,” he said. In other words, at the height of the midterm campaign season, Bush forced Congress to weigh the legal legacy of 9/11, his favored political terrain, and turned the commissions from an abstract debate about constitutional rights into a matter of getting Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to trial. It was a winning gambit, for a little more than a month later, on October 17, 2006, Bush signed the Military Commissions Act into law.

The Military Commissions Act was promptly challenged, and the Supreme Court is expected to rule on the case shortly. The act’s most vulnerable point, from a constitutional perspective, is a provision barring the detainees from filing writs of habeas corpus. The Administration argues that, even if detainees have rights under the Constitution to habeas corpus, the procedures in place at Guantánamo are an adequate substitute; lawyers for the detainees argue that the Administration has fallen far short of justifying the extreme step of suspending habeas corpus. Last December, at the oral argument of the current Supreme Court case, which is known as Boumediene v. Bush, a majority of the Justices—among them Anthony Kennedy, the Court’s swing vote—seemed skeptical of the Administration’s position, and the Court will likely strike down at least part of the Commissions Act. Again, it appears, a rebuke from the Court will prompt not a retreat by the Bush Administration but another attempt to double-down on its aggressive approach to the detainees. The Court’s ruling, in that sense, could be less a legal setback for the President than a political opportunity for his party.

Near Camp Justice, the authorities will use the “pink palace,” an old air-traffic-control terminal, for the trials of detainees regarded as minor figures. But the big trials, like that of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, will take place in the new metal building, in what for the most part resembles a modern federal courtroom in the United States. The defendants will sit at the end of long defense-counsel tables, next to their interpreters, and all counsel will have computers where the evidence and legal filings in the case can be displayed. The jurors, who will all be military personnel, will also have their own terminals. The law requires at least twelve jurors in capital cases, and at least five in commissions where the penalty is less than death. (In February, the Administration announced that it would seek the death penalty on charges against Mohammed and five others; last week, it added a capital case against Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani for his alleged role in the 1998 bombing of the American Embassy in Tanzania.)

In the new courtroom, I spoke to Brigadier General Thomas W. Hartmann, the legal adviser to the Office of Military Commissions, in the Pentagon, and, as such, the chief Administration defender of the commission process. Hartmann, an Air Force Reservist, is in civilian life general counsel to a Connecticut-based energy company. “When this is over, I’d like people to say these trials were conducted as fairly and as consistently as possible, and we followed the rule of law,” he told me, as we sat at one of the prosecution tables.

Hartmann said that the commission procedures mirrored those of courts-martial. “There will be no secret evidence—defendants will see all of the evidence presented to the jury against them,” he said. “If the prosecution wants to use hearsay evidence, it has to give notice to the defense and a hearing has to be held to see if it’s reliable.” Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is required for conviction, and defendants are given a military counsel (and also may hire an attorney), and they do not have to testify, with no inference to be drawn against them if they do not. Death sentences must be unanimous; two-thirds or three-quarters may be sufficient for conviction of lesser offenses.

But there is a heads-I-win, tails-you-lose quality to the proceedings. If a defendant is acquitted, he need not be released; he can simply be returned to detainee status at Guantánamo, to remain in custody until the end of the war on terror—raising the question of what sort of recourse the proceedings really provide.

“What’s unusual about what we’re doing is that we’re having the commissions before the end of the war,” Hartmann told me. “The Nuremberg trials were after World War Two, so there was no possibility of the defendants going back to the battlefield. We still have that problem. We are trying these alleged war criminals during the war. So, in order to protect our troops in the field, in general we are not going to release anyone who poses a danger until the war is over.” By this reasoning, even those Guantánamo detainees who are acquitted of the charges against them are analogous to Nazi war criminals.

The commissions are not, however, the only way for detainees to be released. In the past year or so, the U.S. government has engaged in extensive diplomatic efforts to find acceptable homes for detainees of lesser interest. Hundreds of prisoners have left this way; Saudi Arabia alone took about a hundred last year. In a rather forlorn attempt to control the detainees’ future behavior, each of those released is asked to sign a form that promises, among other things, that he “will not affiliate himself with al Qaeda or its Taliban supporters” and he “will not engage in, assist, or conspire to commit any acts of terrorism.” If detainees refuse to sign, they are released anyway. According to critics, the release of so many detainees in such a short period amounts to an admission by the Administration that the detainees were never as dangerous as had been claimed. “Now that it’s clear that Guantánamo is such an embarrassment, they are just shipping as many of them out the door as they can, and just keeping enough of them to save face,” Clive Stafford Smith, who has long represented detainees at Guantánamo, said. “It’s a political process that has little to do with terrorism.”

Of the two hundred and seventy-five or so detainees now in Guantánamo, about sixty have been approved for transfer, if countries can be found to take them. (This issue is complicated by the fact that the United States has not been able to negotiate handovers to some countries, notably Yemen. Other detainees say that they will be tortured in their home country; cases involving Algerian and Tunisian nationals making this claim are pending in federal court in Washington.) Of the remaining detainees, Hartmann anticipates that there is sufficient evidence to bring commissions against only between sixty and eighty. In sum, there are more than a hundred and thirty detainees for whom Administration officials acknowledge they have no plan, except indefinite detention without trial.

The design of the courtroom itself suggests another problem with the commissions. For trials in America, journalists and other members of the public sit inside the courtroom; in Guantánamo, they will watch from behind soundproof glass, which can be screened off, with the sound eliminated, at any time.

“You know why the courtroom has the sealed-off press section, don’t you?” Stafford Smith said. “All they care about is the evidence of the accused being tortured. They keep saying that the accused will see all the evidence, but the accused already knows he’s been tortured. The point is to make sure that the media and the public don’t see the evidence of torture. The key thing that they say is classified is evidence of torture and abuse.”

That is not how Hartmann sees it. “The window is there in case the prosecutors want to use classified information, and they have advised that there will be relatively little used,” he said. Still, classified information often involves “sources and methods” of intelligence gathering, and details about the interrogations of the detainees are likely to be kept from the public. This, of course, comes in the context of admissions by the government that several of the leading defendants, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Abu Zubaydah, were subjected to waterboarding—the use of near-drowning during questioning. “The statute says that torture is illegal, and statements derived from torture are inadmissible,” Hartmann told me. But is waterboarding torture? “These are evidentiary matters to be decided in the courtroom,” he said.

To try to forestall trials centered on the alleged torture of the defendants, the prosecutors have assembled “clean teams”—investigators who were not directly involved in the interrogation—to build cases against Mohammed and the others which exclude any evidence that might be tainted. “The clean teams are a joke,” Stafford Smith said. “It’s impossible to ‘unhear’ what they said when they were tortured.” But it is true that prosecutors in American criminal trials, when confronted with potentially illegally obtained evidence, sometimes devise ways to present the same facts to the jury. Still, the mere possibility that evidence will be aired about the waterboarding of Mohammed and the others suggests the political, not just the legal, dimension of the commission cases.

“We will all deal with the legacy of Abu Ghraib, but that is not the commissions,” Hartmann said. “The commissions are not the detention facilities, they are not the C.S.R.T.s”—the review tribunals. “They are not even Guantánamo Bay and Camp X-Ray. The commissions are the commissions, and people are going to see that they are fair.”

That claim of fairness suffered a significant blow last fall, when Air Force Colonel Morris D. Davis, the chief prosecutor for the commissions, resigned his post in protest. Davis, who has served as a military lawyer for twenty-four years, took the job in September, 2005. He told me that he operated without interference for about a year. The situation changed when Susan Crawford, a protégée of Vice-President Dick Cheney who is close to his counsel and chief of staff, David Addington, was named the “convening authority” of the commissions and Hartmann took over as legal adviser. Crawford was a political appointee, and her position made her a kind of one-person grand jury. Davis came to believe that Hartmann and Crawford were more concerned with the Administration’s interests than with the integrity of the process.

“The commissions had such a bad image that it was important from the start to do things as openly and transparently as possible, so I spent a long time trying to get evidence declassified,” Davis told me. Crawford and Hartmann, he said, made it clear that they thought that declassifying the evidence was too much trouble and that “we’ve got to get this moving quickly, even if it means doing it behind closed doors.”

Davis went on, “I knew that a few of our likely defendants had been waterboarded, and I just made a decision that we were not going to use any evidence from them that was coerced, and no one challenged that opinion.” But Hartmann, Davis says, questioned whether Davis had the authority to judge the admissibility of evidence.

In the end, it was the structure of the commissions, rather than any single decision by his superiors, that prompted Davis to resign. “I thought the whole idea was for Hartmann and Crawford to be the referees, not beholden to the defense or the prosecution,” he said. “But if Hartmann is in our office each day, assigning lawyers, deciding which cases to bring, what evidence to use, and then supervising the case—that wasn’t right.” (Hartmann denied virtually all of Davis’s version of events; a Department of Defense investigation determined that there was no wrongdoing on his part. Crawford declined to comment on her role. Davis is retiring from the Air Force this summer.)

It remains to be seen if the first two trials, scheduled to open in May and June, will even begin. One is the Hamdan case; in the other, Omar Khadr, a Canadian national who was fifteen years old when he was captured, is accused of killing an American soldier with a hand grenade. Among the outstanding legal questions in these cases are whether conspiracy is a war crime, and whether the defendants, to prepare their own cases, can interview Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other high-value detainees. And there is the issue, also currently unresolved, of whether Khadr should be charged as an adult. Most of the death-penalty defendants, meanwhile, have not yet even been assigned defense attorneys, and their trials are likely months away, at best.

Even if the commissions can somehow begin, the larger question of what to do with the remaining detainees is, for now, unsettled. One response to that quandary is a controversial proposal, by the law professors Neal Katyal and Jack Goldsmith, that is attracting a great deal of attention in the small world of national-security law—and which may offer an electoral lifeline for the Republicans this fall.

Katyal and Goldsmith make unlikely allies. A law professor at Georgetown and former Clinton Administration official, Katyal won widespread renown when he argued and won Salim Hamdan’s case before the Supreme Court in 2006. Goldsmith is a former Bush Administration official who, despite leaving the government in 2004, in part over concerns about civil liberties in the war on terror, remains a strong national-security conservative. (He is now a professor at Harvard Law School.) But the two men shared a conviction that both military commissions and ordinary criminal prosecutions would be impractical for a few of those captured on distant battlefields. Together, they came up with an alternative: a national-security court.

According to their proposal, which was recently the subject of a conference sponsored by American University’s Washington College of Law and the Brookings Institution, sitting federal judges would preside over proceedings in which prosecutors would make the case that a person should be detained. There would be trials of sorts, and detainees would have lawyers, but they would have fewer rights than in a criminal case. Hearsay evidence may be admissible—so government agents could testify about what informants told them—and there would be no requirement for Miranda warnings before interrogations. Some proceedings would be closed to the public. “It’s a new system that’s needed only in extreme circumstances,” Katyal said. “It’s not a default option.”

Civil libertarians are, for the most part, aghast. “It’s the liberals who support this, the ones who should know better, that are dangerous,” Ben Wizner, a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, who has long dealt with detainee issues, said. “The real problem is that there is an emerging consensus that we need to have some legal authority to detain people without trial, and that’s wrong. The government has proved it can criminally prosecute people in terrorism cases—in the African embassy-bombing cases, in the John Walker Lindh case, and others. That’s what the government should do—prosecute them, or release them.” Katyal says, “Would I love every case to be tried in criminal court? Of course. The reality is, when you’re dealing with foreign investigations, particularly concerning events that occurred a long time ago, there are going to be a small handful of cases that you can’t try in criminal court.” Wizner and others assert that the jurisdiction of any new court would be sure to expand and swallow up more suspects for greater periods of time.

In any case, according to lawyers inside and outside government, the Bush Administration may launch a proposal for a national-security court this summer or fall, after what they presume will be its next loss in the Supreme Court. “It looks like when Boumediene comes down the Court may say to the President and Congress that they need more procedures for the detainees,” Goldsmith said. “So, to correct the problem, the President might consider sending something up to Congress this summer or fall. It would help the Republicans in the fall election.” The measure would force congressional Democrats to take a stand on the issue in the middle of the campaign—just as Bush did successfully with the Military Commissions Act after the Hamdan defeat. “It worked very well in 2006,” Goldsmith said. “The only way the Democrats have to not make it an election issue is to give the President the powers he seeks.”

As long as the detainees remain at Guantánamo, the military continues to interrogate them. In this sense, the rationale for the detention center has been unchanged since 2002. Of course, many of the detainees have been talking for five years or more, and it is reasonable to wonder if they have anything left to say.

The head of the Guantánamo Task Force is Admiral Mark Buzby. Moments before he entered a conference room for our interview, an aide brought in the Stars and Stripes and a one-star admiral’s flag and set them behind his chair. Buzby is relentlessly on message about the continuing value of the interrogations. “We ask them, ‘Tell us how you did that forgery stuff.’ That’s as timely now as it was back then,” he told me. “We are filling in the mosaic.” Buzby noted that the detainees’ interrogation sessions were sometimes catered by the base’s fast-food outlets. “They want those Subway sandwiches!” he said. “Sometimes they just want to talk. Meanwhile, he’s chomping on his Subway B.M.T. It’s all about that give-and-take and that rapport-building. We still get regular questions in for us to ask from the front in the field. We’ll show him a map: ‘Thanks a lot, have a Big Mac.’ ”

It is hard to verify such assertions, because the task force does not allow access to the detainees or to the information they provide. However, many detainees who have been released, and the lawyers for those who remain, contend that the continued interrogations amount to harassment of people who never knew anything of intelligence value in the first place.

Still, the question now, as Buzby acknowledges, is whether Guantánamo, as a symbol and recruiting device for terrorists, endangers more lives than it can possibly save. “It’s really for others to weigh whether what we do here is of sufficient value to offset how this place is viewed internationally,” Buzby said. For the man in charge on the ground at Guantánamo, the situation with the detainees has devolved into, at best, a lingering standoff. “I don’t think any of us envision that they will be here in thirty years, but the question is what to do with them,” he said. “The good news is, we got ’em. The bad news is, we got ’em.” ♦

Original here

The simple answer is distraction. The public and the media are so focused on the contrasting policies of Hillary and Bush that little is said about their character. Bush is for as little government intervention as possible and belongs to the part of the party that reiterates that whatever the government does the private sector does better. His failures are so large that some see a devious attempt to make the government fail to prove his point. Conspiracy theories aside, the fact is that his performance failed to achieve Republican goals. Launching a war on false pretense, having it stretched beyond our worse predictions, failing to equip our soldiers, treat them well when they return home -- these are merely few of Bush's administration failures. Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, believes in government intervention more than other Democrats. Whereas Bill Clinton pulled the party to the center and enacted policies that limited government aid, Hillary believes in strong government role both in health care and in her recently announced plan to bail our home owners who cannot support their mortgage. In glaring contrast to GW, Hillary is articulate and has a good public presence.

The simple answer is distraction. The public and the media are so focused on the contrasting policies of Hillary and Bush that little is said about their character. Bush is for as little government intervention as possible and belongs to the part of the party that reiterates that whatever the government does the private sector does better. His failures are so large that some see a devious attempt to make the government fail to prove his point. Conspiracy theories aside, the fact is that his performance failed to achieve Republican goals. Launching a war on false pretense, having it stretched beyond our worse predictions, failing to equip our soldiers, treat them well when they return home -- these are merely few of Bush's administration failures. Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, believes in government intervention more than other Democrats. Whereas Bill Clinton pulled the party to the center and enacted policies that limited government aid, Hillary believes in strong government role both in health care and in her recently announced plan to bail our home owners who cannot support their mortgage. In glaring contrast to GW, Hillary is articulate and has a good public presence. If the current Democratic primaries taught us anything, it is that Hillary Clinton is similarly tenacious, unwilling to compromise, to admit mistakes, to give up when odds of winning are so slim as to become unrealistic. She seems to pursue her own interests with total disregard to the damage she inflicts on the Democratic party.

If the current Democratic primaries taught us anything, it is that Hillary Clinton is similarly tenacious, unwilling to compromise, to admit mistakes, to give up when odds of winning are so slim as to become unrealistic. She seems to pursue her own interests with total disregard to the damage she inflicts on the Democratic party.![[Mary Lyn Villaneuva]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GL815_Villan_20080408173336.gif)

![[Gregory Pierce]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/HC-GL816_Pierce_20080408173343.gif)

![[The Trouble With Brand Hillary]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-BG484_oj_zel_20080408214253.jpg)

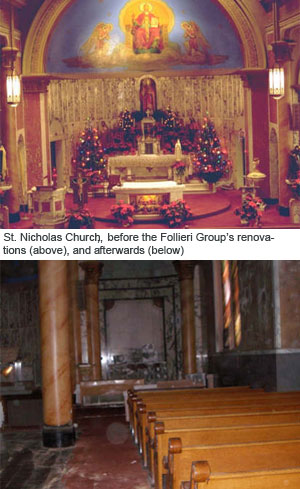

As part of his plan for the property, Follieri had the church undergo massive internal changes. In the spring of 2007, all religious objects including the altar and statues were removed, and the murals were painted over. The community reacted with uproar.

As part of his plan for the property, Follieri had the church undergo massive internal changes. In the spring of 2007, all religious objects including the altar and statues were removed, and the murals were painted over. The community reacted with uproar.